Ebola is only the Kardashian of diseases if you think Africa is a country

Kim Kardashian in 2008. Photo by Dan Raustadt shared w/CC license.

This post is co-authored with Stéphane Helleringer (@helleringer143).

*****

Yesterday Chris Blattman wrote a post titled, “Ebola is the Kardashian of Diseases.” He had tweeted the same thing a day earlier, followed by “Do not get distracted. Malaria, TB, HIV is what matters.”

[Sidenote: For those who don’t know what a Kardashian is, it roughly translates to being famous for no substantive reason (see a helpful description in the third paragraph of this paper).]

While there’s a bit in Blattman’s post to agree with, we find rather misleading one particular point:

-

Meanwhile, malaria, TB and HIV/AIDS are already at pandemic proportions and I venture destroy more lives, more economies, and perhaps even more politics than Ebola.

As global health researchers, we are well aware of the top causes of death in African countries and the data are clear that across the continent, malaria, tuberculosis (TB), and AIDS will each claim more lives this year than will Ebola.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated there were 596,000 deaths from malaria and 230,000 deaths from TB in Africa in 2012 and UNAIDS estimated there were 1.1 million AIDS-related deaths in Africa in 2013.

As a comparison, the total number of Ebola deaths in the current outbreak in West Africa according to the most recent WHO update (8/22) is 1,427. A new, unrelated Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo has left another two people dead. But even considering there will be more deaths from Ebola before year’s end, the total number of Ebola deaths on the African continent will come nowhere close to the numbers of the top killers.

But Africa is a continent – not a country. If a health problem is only prevalent and problematic in one country rather than in many of Africa’s 54 countries, does that make it as irrelevant as a Kardashian? Continent-wide metrics can mask dramatic impacts of disease outbreaks in countries or even sub-regions. If we consider Ebola in the context where it’s unfolding, it matters a great deal. By the end of 2014, it may matter even more in these countries than the other infectious diseases mentioned by Blattman.

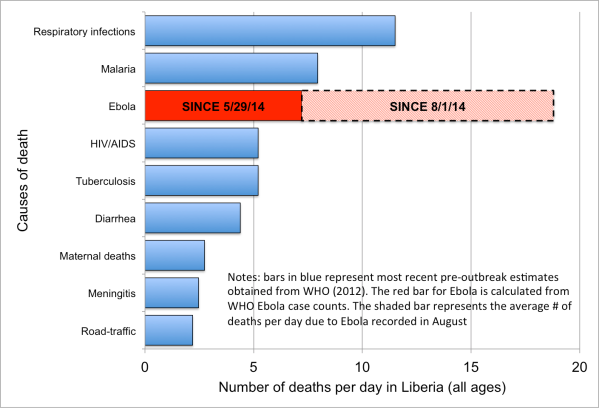

Counting deaths is hard. There are virtually no real-time mortality data in these countries outside of the Ebola case count. What we know about mortality levels and causes in Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia comes either from censuses (conducted every 10 years) or from surveys conducted only every five years or so or from statistical models used by the United Nations and other organizations. So we used the 2012 estimates for the leading causes of death in Liberia published from the WHO to put the current Ebola-related mortality in perspective. It shows that, since 5/29, the daily number of Ebola deaths is comparable to the daily number of malaria deaths (approximately seven per day) prior to the outbreak. The daily number of Ebola deaths recorded by WHO has been increasing steadily: in August, it reached an average of 18 deaths per day. This is higher than daily averages for any other cause of death in the country. And it seems to continue climbing (see figure below).

Maybe a reader will be suspicious in reading too much into our daily death rate graph since these data may be capturing a temporary spike in the number of deaths. Over an entire year, the “big killers” that matter could still very well dwarf the total number of deaths due to Ebola. But the current Ebola outbreak is not going away without a fight. The international director of Doctors without Borders said recently that the situation is spiraling out of control in Liberia and Sierra Leone. The outbreak has had a slow and unimpressive response from governments in the affected countries and from the WHO. The heavily affected countries have incredible health care worker shortages and, as more health workers get infected, there will be even fewer to care for those who become sick with Ebola. Just today, the WHO announced it was temporarily pulling its health workers out of Kailahun in Sierra Leone after one of its staff members contracted Ebola under incredibly challenging working conditions.

So, how many deaths from Ebola can we expect by year’s end under these conditions? To try and answer this question, we did some simple arithmetic: at a rate of 18 deaths per day (i.e., the average number reported for August so far in Liberia), it will only be 10 days until Ebola has killed as many people as road-traffic accidents usually kill in the country in an entire year. It will be 20 days until Ebola reaches the yearly level of maternal deaths; 70 days until it reaches the number of deaths from HIV/AIDS deaths and 125 days (i.e., before the end of 2014) until it reaches the estimated annual number of malaria deaths in the country. And of course, these “projections” rest on the very optimistic assumption that the public health response will be able to maintain the number of deaths due to Ebola at 18 per day. In recent days however, the daily number of deaths seems to have been rising quite sharply over time. The number of Ebola deaths may thus catch up with other causes of death this year much sooner than we just calculated.

We have not calculated similar measures for Guinea or Sierra Leone – but given the wealth of publicly available data, we hope others will. Based on reported figures, the outbreak appears better controlled in those two countries and the number of Ebola deaths may not catch up with other causes of death like HIV/AIDS and malaria. It might also be instructive to consider the three countries together in a comparison of the impact of the major causes of death.

But one should still be cautious in sub-regional comparisons. These, too, can be misleading. For example, The Economist called Ebola a “small-scale killer” when comparing it to other infectious diseases in the four affected countries: Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Nigeria (at the time of publication, there had not yet been news of the unrelated outbreak in the DRC).

The inclusion of Nigeria in The Economist’s figure, however, biases the assessment of the scale on which Ebola strikes, for two reasons. First, Nigeria has experienced only a very limited number of Ebola cases: 11 infections resulting from one recent “importation”, at the end of July (i.e., contact with an infected traveler, Patrick Sawyer, who flew to Nigeria from Liberia). Later, two infections resulting from contact with patients who came into contact with the index case (for a total of 14 confirmed Ebola cases) were also recorded. Second, Nigeria is also the most populous country in Africa; its population is more than eight times larger than that of populations of the other affected countries combined. As such, any estimates of deaths per day that includes Nigeria in a sub-regional analysis will be heavily influenced by the data from Nigeria.

Two additional points to keep in mind:

- Despite the very exact counts for Ebola cases published with regularity by the WHO, these cases are very likely an undercount. The WHO even stated recently that their estimates of the number of Ebola deaths likely underestimate the scope of the outbreak. So if that is the case, Ebola may reach the level of other causes of death even faster than we calculated above.

- This post is ONLY about deaths. Ebola has taken a much larger toll on these countries than through deaths alone. Think of the effects Ebola is having on the local economies in the most heavily affected countries. HIV/AIDS and malaria are serious diseases – but they haven’t stopped commercial airliners from flying to West Africa.

In sum, we know that the Ebola outbreak is unfolding in a context where there are indeed many pressing issues facing the ordinary folks who are themselves trying to navigate the outbreak. Though we appreciate considering the broader continental context, one might generate misleading characterizations of the impact and scale of Ebola when thinking of Africa as a single unit.

Trackbacks

- Graphic Monday (…well, Wednesday): Vox’s Donations vs. Disease Graphic | A Crowing Hen

- Ebola roundup #1 | Constrained Optimization

- The politics of intervention choice: HIV, enteric diseases and Ebola – Raul Pacheco-Vega, PhD

- A Few Readings on the Ebola Outbreak | Cryptic Philosopher

- Did Spain Just Screw the Ebola Pooch? | Compromise and Conceit

Comments are closed.

The central thrust is hard to disagree with: “If a health problem is only prevalent and problematic in one country rather than in many of Africa’s 54 countries, does that make it as irrelevant as a Kardashian?” But, despite its catchy cleverness, the title is sparring with a straw man. Blattman’s point is based specifically on the variation of “state capacity” across Africa’s 54 (/55) countries (and indeed beyond: he seems just as interested in the fact that “A Western country could contain an outbreak”).

The title also seems to normalise the nation state as the appropriate “container” for concern: the implicit assumption is that because Blattman is thinking on a continental scale, he must think that Africa is a “country.” @dadakim’s argument, conversely, is that rather we should “look @ country-level.”

The point that “If we consider Ebola in the context where it’s unfolding, it matters a great deal” is unarguable, but the post here provides no reason why that context should be at the “country-level” specifically. The point about context would be equally valid if the outbreak was in fact only in one province: it would matter a great deal in the context of that province. Come to that, even if there was only one victim, it would “matter a great deal” to that one person. Beyond the incalculable personal tragedy of the death of any human being, any loss of life is going to “matter” “more” if we reduce the total set from which we calculate the deaths as a proportion (hence the argument about the inclusion – or not – of Nigeria in sub-regional analyses). What’s important is that we define an appropriate “set” and in the end that comes down to how we’re defining what “matters.” Blattman provides some very general pointers as to what he thinks matters: the “economies” and “politics” “destroy[ed]” by loss of life. That’s pretty vague, but it’s more specific than anything offered in this critique.

If you examine the WHO numbers of infections in Liberia for the last two month periods to resolve a working infection rate increase per month, you get a 4 to 5 times increase per month. If that continues (and given the out-of-control situation in Monrovia & the rest of Liberia) then future months will likely be a worst case scenario. When you do that math, you end up with ~105,000 infections for November and ~480,000 infections for December. If you use the ‘only 25 to 50%’ reported figure given by WHO and Ken Isaacs, then those maximized numbers become 420,000 and 1.9 million infections in Nov & Dec. Clearly Liberia & the disease will not withstand such numbers and changes will ensue one way or the other.

We all need to rapidly get moving on an effective response to this disease in all affected countries but for Liberia most of all. Effective treatment, contact tracing and quarantine are impossible with the above kinds of numbers.