weighing in on using electronic devices to collect survey data

Folks at the Development Impact blog wrote a two-part series on the benefits and drawbacks of using traditional pen-and-paper surveys or surveys administered using an electronic device (often referred to as CAPI, which is short for computer-assisted personal interviewing).* My own experience using CAPI in 2011 and again in 2012 mirrors some of the benefits and drawbacks highlighted by Development Impact. In this blog post, I summarize the series by Development Impact, introduce the CAPI format I’ve used for surveys collected in Malawi in 2011 and 2012, and weigh in with my own thoughts on CAPI.

Part I of the Development Impact series highlights the benefits of CAPI:

- enumerators can get instant feedback on their performance

- cleaner and easier to track

- get data faster

- ability to get more confidential data

- monitoring with date/time/GPS location stamps

- easier validation for survey design improvement

Part II of the Development Impact series highlights the drawbacks:

- simple mistakes can be very costly

- high start-up costs (programming, piloting, training)

- data can get lost

- data security

- potential device failure

- dependence on electricity

- limited empirical evidence on the improved data quality

In 2011, I fielded a small survey (N=205) in a rural area of Zomba District, Malawi. I had purchased 4 iPads (1st generation refurbished wifi-only 16GB models, sold at a reduced price** on Apple’s web site following the release of iPad-2).

I tasked a research assistant with identifying potential software options. We ultimately decided on iSurvey, which offers a free app from the App Store, unlimited survey questions, unlimited survey observations, to be used on as many devices as you wish. The cost was a monthly payment of $89 for a survey. A primary benefit of using iSurvey is that surveys are created using their web site, and their current version allows for a lot of different options (grids, skip logic, image use, etc.). iSurvey does not require programming skills, just someone who knows how to navigate a web page. The process of linking an iPad to a given survey on iSurvey is rather simple, and once a survey has been completed on an iPad, the data will be uploaded to iSurvey’s server (pending an internet connection, of course). Once data are uploaded, you can download CSV or SPSS versions of the data from iSurvey’s web site.

In 2011, iSurvey and iPads in the field worked incredibly well. There were only a handful of evenings when we couldn’t upload data from the iPads because of our lack of an internet connection,*** and on these nights, we backed up the iPads to our project laptop to ensure data weren’t lost (or, at least, it made us feel better about not being able to upload the data to the cloud). There were a number of electricity outages during August 2011, so we were diligent about charging batteries when we could and carried a vehicle inverter and fully charged laptops (to funnel charge via the USB port to iPads) with us in case we had to charge them in the vehicle on our way to the field site. Each night we uploaded data, we also downloaded data — to see if there were odd patterns or problems with specific questions or interviewers. Any problems or inconsistencies were discussed the following morning with the field team before going out for another round of interviews.

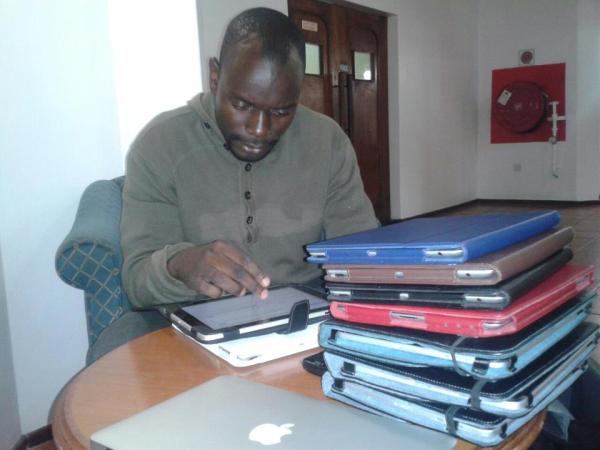

Field Supervisor Augustine Harawa working among a stack of 9 iPads during 2012 data collection. Photo by Tara McKay, shared with permission. (All rights reserved.)

The 2012 implementation was not so smooth. No one in the field in 2012 had any previous experience with the back-end of iSurvey and only the field supervisor had used the iSurvey app in the field previously (but he had joined the 2011 team late, when we were nearly done with the survey interviewing segment of data collection). Internet connections were difficult to come by, especially when the team left Zomba for more rural districts in our sample. I would check the data from the US, but with the time lag (in terms of uploading and the 7-hour time difference between Malawi and Texas) and difficulties with communicating to the Malawian team, there was not the same fast turnaround as when I was in the field checking the data each night and talking to the field team the following morning. There was also a larger field team (9 interviewers/iPads in 2012, compared to 5 in 2011).

One of the benefits mentioned by Development Impact is the ability to monitor with time stamping — and iSurvey allows for this. Given some of the timestamps I saw in the data, however, it seemed to me that some interviewers were “cheating.”**** This led to a serious fissure in the research team, to a point where I couldn’t even talk to them because it was making me physically ill debating what was really going on. Though the iSurvey team were responsive to our requests for more information about the timestamps and how unusual they seemed, the matter was never resolved. Given the tense situation it created, I’m still left wondering whether I want to know if data has been faked… but there is sufficient content for an entire post (or series!) on data validity that is certainly not limited to CAPI.

In sum, I would definitely want to use iSurvey/iPads again, but I am hesitant to implement in the same way it was done in 2012. Development Impact is correct in saying: “There is no computerized substitute for a well-designed, well-supervised field work effort.” I think we probably had too few people managing data collection in the field, especially anyone with the time or skills to take care of back-end data checking in-field. One of the benefits of paper surveys is that a supervisor can sit in a vehicle all afternoon and read through the surveys done by interviewers and identify problems (and immediately send interviewers for “call-backs” for anything serious). Though I felt I could easily manage data-checking from afar with a team run by people I knew well and had worked with before, there is always a great distance between people collecting data and people sitting in air-conditioned offices in the US (in addition to challenges posed by the aforementioned time lags for data uploads). This distance isn’t just a physical one. There is something about being there in the midst of it all that gives you a different sense of the data and of the team collecting it. In fact, when I pursued the alleged cheating incident, one email I received pointed out that I was not “even in the field.” As a field researcher, that is one of the worst things you can hear about yourself. But in fact, it was correct. Just because CAPI allows you to see the data in “real-time,” it doesn’t necessarily bring you closer to the subject of study.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

*This topic is not so new to development blogs — see, for example, this post from the previous decade, written by light-years-ahead researcher Chris Blattman.

**It does not take infinity billion dollars to use CAPI in the field. For me, the start-up costs were $349/iPad and $89 for the software. Data entry costs: $0. Of course, if you’re a broke graduate student, you might be entering the data yourself (in addition to cost-saving benefits of entering the data yourself, you also get to see all of the data, which is helpful). If the costs of purchasing iPads (or whatever device it is that you choose) is something your budget can’t cover, you might also consider borrowing from someone else who has them. I am happy to loan mine out to other field researchers when I’m not using them.

*** Malawi is not like Kenya and our iPads were 1st generation, meaning we couldn’t just connect via a 3G connection. Instead, we connected via a broadcasted signal from a Mac laptop that connected via a dongle.

**** By “cheating” I mean it looked as if there were interviews that were not with real people, but rather made-up data. This was never confirmed.

Nice discussion of our issues in the field.

I might also add to the discussion of drawbacks that the dependence on internet led to several interruptions in fieldwork where we had to scour the earth for internet before we administered any more surveys (we didn’t back up onto the MacBook. I thought we had discussed how this wasn’t possible?). While in the field, on at least two occasions, we went more than three days without finding internet on dongles, phones, internet cafes with wifi (necessary because the new MacBook Air doesn’t have an ethernet port), and fancy hotels. Further, during the pilot while we were still updating the survey, the lack of readily available internet to update the survey in the field meant that we lost an entire day of pilot data (since it could not be merged with the new survey. This inability to merge/retain data after changes to the survey in iSurvey is a drawback that seems otherwise undiscussed above and which was a major issue for us.) Although, because you now have 9 ipads, it is unlikely you will switch platforms, IKI has been using android phones to collect data for some surveys. In whining about the problems we were facing during the pilot and first week of fieldwork, I was frequently told about how the android platform, since it was not web-based, did not have the issues we had. Phones could be used to collect data and then be uploaded directly to a laptop in the field for review. Battery life seems similar. Screens are, of course, much smaller and fingers much bigger in relation to question responses. Programming also seemed more intensive and question response options less interesting. BUT the lack of dependence on the internet to retrieve data is a huge advantage here for people who are still considering what to do.

In terms of device failure, there were multiple unexpected issues with ipads turning themselves off for no particular reason, app crashes and lag (the infamous “Loading” screen that could last for minutes in the middle of an interview), and even ipad overheating. If interviews were conducted outside in areas without much shade, a handful of savvy interviewers would increase the brightness on their machine to 100%. While this certainly makes reading the survey easier, on the older ipads, it ensures that they will not be able to complete more than 6 interviews on a full battery. Many days, interviewers were assigned 7 or 8 interviews for the day. The interviewer who increased the brightness, even though every day I returned it to 40% and told him not to touch it again, completed fewer interviews than his colleagues and was more frequently unable to complete the allotted number of interviews for the day.

As for data collection, there are several places where iSurvey improves over a paper-pencil survey. Many of the interviewers commented on their exit surveys (sorry, I know I still need to send these to you. they are safe.) that ipads are a bit faster (except for the few who frequently had the “Loading” problem) and that mistakes are not “expensive” – as in they can return back it check and correct. With the data entry requirements, missing data for a question was accidentally skipped is just not an issue we have. ALL of the interviewers prefer ipads over paper surveys. However, for things like text-boxes, time constraints, lack of typing skills and less proficiency with English together promote a situation where the interviewer writes as little as possible and often repeats the same well-known phrase. We see this multiple times in our data, from my question, to your list of problems, to the comments at the end.

Given that the interviewer can go back a screen if they make a mistake in data recording, I would have expected that we would have had fewer of the mis-selected options mistakes (this was also a key benefit of ipads that interviewers identified). However, perhaps because of the novelty of digital data collection for the interviewers, we had several mistakes that you just wouldn’t find on a paper-pencil survey – e.g., respondent’s gender.

Like this mistake, I think most of the mistakes interviewers made began as fixable. However, the substantial delay from using a web-based survey application ensured that by the time we found errors in the data, the interviewers no longer remembered the interview in as much detail as we would need to fix the mistake. This encouraged the adoption of a parallel and increasingly time consuming pen-and-paper summary of each interview that interviewers recorded in their notebooks and that were then copied into a supervisor’s notebook at the end of each day.

Additional benefits: it was amazing to not have to find a printer or carry one. It was amazing to not have to keep track of 1600 paper surveys, many of which would eventually be torn, unstapled, unmatched, and unusable.

I’m not committed to the iPads just because I already have them (sunk costs and all that). I liked them so much because they were so successful in 2011. I would actually have preferred in 2011 and 2012 to use ODK/Android devices (Android devices are cheaper and ODK was created by a Ghanaian!). I was unwilling, however, to learn how to program and I didn’t have the budget to pay someone else to program the surveys. iSurvey would allow for changes from afar whereas I doubt ODK would have been as easy to fix problems or change the survey without the [expensive] programmer being in the field.

Has anyone done any experiments testing data-entry on the fly approaches like this to pen & paper approaches for response (in-)accuracies? I have plausible scenarios generating expectations in just about every direction about that question, but is one thing i’d like to know more about before implementing something like that on my own. E.g., are there good “oops, that’s not what i meant to tick” options? How much more difficult is that if you have self-administered surveys, etc. I’m sure there’s tons of research out there on this, but you opened the can.

jimi – see this experiment in TZ comparing CAPI to pen-and-paper interviewing:

Click to access Caeyers_Chalmers_DeWeerdt_JDE.pdf

This is really useful to know, especially about the potentially lower prices that are out there. The Development Impact posts implied extremely high costs, as did all the folks I talked to about this in Lilongwe. But now I’m thinking most of that is the cost of hiring someone to program the devices; I’d insist on doing that myself anyway, or having a collaborator that does it. Looking at my budget, it looks like it would cost about double to do it via CAPI, and that’s if I had to buy my own devices. Renting might be cheaper. Were I to write that post again I might call it “Things I would do if I had written them into my initial IRB application and/or had time to pull off an amendment.”

The other glitches and difficulties are also valuable information. I think dirt-cheap netbooks are the future of this, since they don’t require typing stuff on a tablet. I can type like the dickens on my iPhone using both thumbs and sideways mode, but I’ve never found a tablet where I can pull that off.

The rule against buying durable goods in most grants has got to go; this stuff is the future, and funders need to catch up.

There’s no real programming costs for iSurvey (and I’ve heard ODK has a web interface that one can use now as well). That’s not to say the learning curve is zero, just that anyone with experience browsing the web and some patience could easily figure it out.

I find typing on an iPad rather easy… but there’s also not much one has to free-type in a survey; good surveys won’t have many open-ended responses. I would upload a screen shot (that demonstrates how easy it is to make selections), but I don’t have the iPads back yet.

You’re right about glitches and difficulties as valuable information. For example, the glitches can provide one measurement of interviewer quality.

That’s a pretty huge contrast with Aine McCarthy’s experience with Pendragon (which parallels what I’ve heard from others about that software) – she says she’s been programming it full time for 5 weeks. [http://ainesmccarthy.weebly.com/1/post/2012/08/enumeration-training-and-capi.html]

Are the iPads you used able to automatically record GPS coordinates?

JK: technically iPads would be able to record GPS coordinates (either as part of iSurvey or some other free app), but the iPads I actually have are wifi only, so would only be able to do that if there was wifi at the location of interview. In Malawi, that’s like no where we conducted an interview. 😉